The images that come to mind when we think of “reclaiming democracy” tend to drift toward hoards of protesters storming barricades, or a triumphant election-night speech to a crowd of supporters.

Less celebrated are the decidedly unsexy decisions made over a city’s budget. But—inspired by experiments in democratic budgeting in Brazil—cities around the United States are turning to something called participatory budgeting to put funds toward the projects politicians won’t.

In light of the austerity that has wracked municipal governments the last several decades, participatory budgeting offers ordinary people a way to engage in an increasingly key facet of government. Since its founding in 2009, the Participatory Budgeting Project has allocated $98,000,000 in public money, engaging 100,000 people in 440 local projects around the country. While overseeing relatively small slices of funding, participatory budgeting (PB) processes are designed to bring out more than the “usual suspects of local governments,” creating broadly accessible platforms that redefine that nature and impact of civic engagement.

To hear more about this, NEC sat down over the phone with PBP’s Data & Technology Manager, Asuum Mulji, who spoke to us from his office in Oakland.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity

-------------------

NEC: What is participatory budgeting?

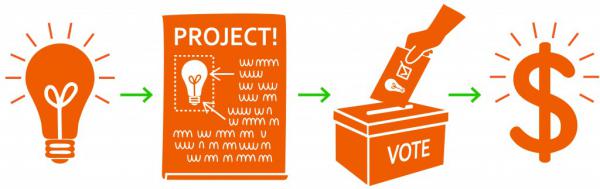

Aseem Mulji: Participatory budgeting (PB) is a democratic process for people to directly decide how to spend a public budget. It can happen anywhere where there’s a public budget that needs to be allocated from year to year. It typically takes place over a couple months and it’s a cyclical process. The way the process works is people come together in large public assemblies to brainstorm ideas for how a portion of the public budget can be spent. A group of volunteers will take all those ideas, work with city and administrative staff to turn them into concrete proposals, and then finally take those projects to the public for a full community-wide vote. After that, the government will implement the budget, then ideally the next year start the process again and on an annual basis. It’s really rooted in not just getting people to voice their concerns, but to make real decisions about real money.

NEC: How did PB come about?

AM: The model of PB that we talk about when we advocate for it here in the U.S. is a model that was started 25 years ago in Porto Alegre, Brazil. The Workers Party came to power in Porto Alegre specifically with a mandate to address extreme inequality that the city was facing, and that parts of Brazil continue to face. They identified a large chunk of the budget, particularly for large communities of low-income populations to decide to spend through the PB process. They found that PB has contributed to their formation of civic infrastructure where there was none, and concretely expanded road and sewage coverage to cities that don’t have it. This is the model of PB that we’ve tried to evangelize and deepen here in the U.S.

About five years ago, an alderman in Chicago heard about PB at the World Social Forum. He brought on our organization to help them do the first participatory process in the U.S. We spent $1 million of money he had at his disposal to do infrastructure projects. After that first experiment in Chicago, city council members in New York decided to come on board to do PB. Since then, PB in New York has really expanded quite a lot. Now over half of council members there are using PB to allocate their discretionary money in their districts for capital projects.

Since then, we’ve had cities like Vallejo [California] come on board to do a citywide process. Other cities that are doing PB now are Boston, a youth-centered process where youth ages 12-25 are deciding how to spend $1 million; Cambridge, Massachusetts; Seattle; Greensboro; cities in Canada; small cities, large cities. We’re really seeing an explosion of interest in PB, especially at the municipal government level.

NEC: How does PB influence other decisions the city makes regarding budget?

AM: PB typically addresses a small budget that clearly needs to be reallocated from year to year. But one of the biggest impacts of that we lift up is the possibility for PB to be used as a tool of democracy. We find that some low income, marginalized communities that have never had a voice in local government develop skills in facilitation and public speaking, through PB. So we’re able to build infrastructure and new community leaders to advocate for other policies with larger portions of budget. PB has been done for up to 20% of city budget. There’s no reason why we can’t make budgeting more democratic.

We talk about different strategies that make the process more accessible to low income residents and people not usually at the table. The first is rooting processes in grassroots leadership. Each PB process has a steering committee that is responsible for government and working with city government on implementation. Having folks sit on the steering committee who already work with marginalized communities is extremely important.

The second strategy is designing process in way that makes it accessible. This includes holding voting at locations outside of city hall where groups who don’t typically show up gather, lowering the voting age to below 18 so youth can participate, opening the process to people who are undocumented and people who have felonies on their record, and outreaching to those groups in particular.

NEC: Given your background in civic tech and role within the Participatory Budgeting Project, I’m wondering how technology fits into this? What are the most exciting applications you see? What kinds of opportunity does technology present to PB?

AM: Technology and data hold a lot of potential to scale our impacts. But also we feel very strongly in the power of in-person engagement —building relationships to make engagement fun. So we’ve approached integration of new technology cautiously. For the past two years we’ve been working with a lot of technology partners to year to try out tools, games and new methods under new processes. We’ve also developed guiding principles for integrating online engagement in PB.

One tool helping maximize engagement of traditionally marginalized groups is reducingg the administrative burden of doing PB on coordinating staff, so that they’re not spending a ton of time on tests that a computer program could do, and they can do the more important work of relationship building and organizing which are key to any successful PB process. At the end of the day, technology should help make PB more accessible and help people make more informed choices.

One of the big tools that we’ve been trying to lift up is using text messaging, or SMS to do outreach during PB processes. In Boston, we’ve been able to successfully establish the new SMS tools, helping connect hard to reach populations, like youth and immigrant groups, and people who don’t have a lot of access to computers to these civic opportunities. We’re now supporting SMS engagement in New York, Long Beach, Greensboro and other cities as well. We asked youth how they wanted to be communicated with, and by and large they preferred text and meeting reminders. We’re looking into really increasing engagement of marginalized groups to level the playing field through the communications platforms we use.

NEC: How does PB look like in Vallejo?

AM: Vallejo was the first PB process at the city-wide level. They set aside 30 percent of a portion of revenue that was $3.4 million between 2012-2013. That measure is now entering its third cycle. It’s considered to be a success because it’s fairly institutionalized in government. In the first two years when we were involved, nearly 4,000 people came out to vote. It was a big success. It was the highest participation rate of any PB process at the time.

People sometimes ask, if PB is only bringing out 1-2 percent of the population, is it worth it? We try to put PB into some perspective. We ask people to compare PB to other activities for regular budget participation, like a budgetary hearings, for example, where there may be 50 people in room. We find that PB is a huge step up from a lot of existing budget participation. Vallejo is good example of that, especially in a city where trust between government and people had been compromised. During the recession, when the city had to file for bankruptcy, PB allowed government and people to come together and start to come to trust again slowly but surely. People have seen PB as an intervention to change the tone and the culture of governing. A goal of PB is to really institutionalize process to make it a regular part of governing.

Aseem Mulji manages the Participatory Budgeting Project’s data and technology projects, and also helped implement the first city-wide PB process in the US, in Vallejo, CA, and he continues to support PB processes in California.

Aseem Mulji manages the Participatory Budgeting Project’s data and technology projects, and also helped implement the first city-wide PB process in the US, in Vallejo, CA, and he continues to support PB processes in California.

Follow us: Twitter YouTube Facebook